Several of the books I read this read this year included lovely, magical, memorable Christmas scenes. The holiday memoirs of three authors in particular stood out for me, all from approximately the same time period but celebrated in very different ways, according to economic circumstance.

1a. In Harry's Last Stand, Harry Leslie Smith (b. 1923, Barnsley, United Kingdom) recalls a British depression - era Christmas, the last year that his father was physically able to work full - time as a miner:

42 - 43: "Yet despite the cold gloom and half - light of winter, that Christmas (1926) was as close to magical as I can remember from my childhood. We celebrated and defied our poverty, our mourning over Marion and our anxiety for the future with passion and happiness at being in each other's company.

"On Christmas day, my father entertained us by playing carols on the piano while my mother prepared a goose. Our feast had been bought at the expense of my mother's wedding ring that had been put in hawk at the pawnbroker's shop. For a present, I was give a toy train engine that my parents were never able to equal in extravagance during subsequent Christmases. In the years that followed, my sister and I would speak of that Christmas as if we had received the riches of Croesus from our parents, because it was one of the last moments that we remembered our family being truly happy."

112: "And even though times were rough, he [my father] tried to make the most out of family life. I remember the excitement of once seeing a Christmas panto, or going to the seaside with my family. I remember in particular one bank holiday outing to Southport." [Where Gerry and I, along with Gerry's parents, took Ben and Sam several times to see the panto; and Gerry before them; and Gerry's mother before him!]

~ from 1947 until her death in 1999 ~

1b. In Love Among the Ruins:A Memoir of Life and Love in Hamburg, 1945, Harry Leslie Smith (1923 - 2018) includes a beautiful chapter (#12 "Stille Nacht"), describing the Christmas Eve of 1945 when he remained stationed in Hamburg, Germany, following the war. He celebrates with his fellow soldiers during the afternoon, and later that evening at the home of his German girlfriend Friede:

118: "It snowed on Christmas Eve. It fell like icing sugar and dusted the city as if it were a stale and crumbling Christmas cake. The pedallers, black marketers, and cigarette hustlers scrambled to finish their commerce before the church bells pealed to celebrate the birth of Christ. Along the St. Pauli district, steam-powered trucks delivered beer and wine to the whorehouses, who expected exceptional business from nostalgic servicemen. Across the Reeperbahn, the lights burned bright, while in the refugee camps, the homeless huddled down against the cold, warming themselves with watery soup and kind words provided by visiting Lutherans priests."

119 - 20: "This was a unique Christmas because for the first time since 1938, the entire world was at peace. So anyone who was able took leave and abandoned our aerodrome for a ten-day furlough. For those of us who remained, a Christmas committee was formed to organize festivities. The Yule spirit around camp mirrored row house Britain. It was constructed out of cut-price lager and crepe paper decorations with the unspoken motto: 'cheap but cheerful cheer in Fuhlsbüttel.' In the mess hall, a giant Christmas tree was erected dangerously close to a wood stove by the Xmas team. They had festooned it with glittering ornaments and placed faux presents underneath its boughs. Sleighs and Father Christmas figures cut from heavy paper were pinned to the walls as festive decorations. Mistletoe dangled from light fixtures and gave our dining hall the appearance of a holiday party at a carpet mill in Halifax."

"On the morning before Christmas, I negotiated with the head cook for extra rations for Friede and her family to allow them a holiday meal. The cook was an obliging Londoner whose mastery of culinary arts began and ended with the breakfast fry up. Never one to saying no to sweetening his own pot, the cook amicably took my bribe of tailored shirts in exchange for food. He let me fill my kit bag to bursting with tinned meat, savouries, and sweets. . . . pork pie along with a bit of plum pudding . . . some cheeses."

121; 128: "So everyone [at the army base] agreed -- including me -- that the holidays at home were magic, and we drank more beer to celebrate those ‘bloody magic days of youth.’To myself, I thought Christmas was more witchcraft than magical in the ‘dirty thirties,’ but I wasn’t going to spoil this celebration by denying their belief in happy childhood memories. . . . I lied and said, ‘On Christmas Day, my Mam puts out a roast goose with all the trimmings,’ whereupon everyone enviously applauded my fictitious family festivities."

125: [Later at Friede's, she confides in him], "‘I want this holiday, this New Year to be special. During the war, Christmas was very sad with so many causalities at the front and so much destruction around at home. I never felt safe and it never felt particularly joyful.’"

127 - 28: "When dinner was called, the [neighbors] brought out a gramophone and set it up in the kitchen. Over dinner, we listened to ancient pre-war 78rpm discs of German carols or nostalgic songs about Hamburg sung by soloists. During the meal, there was an element of make-believe to our conversation and in the expression and gestures of the diners. Between mouthfuls of soup and warm bread, my hosts remembered and relived old Christmases when there was no war and their life was not dictated by occupation. [They] laughed at old worn jokes. They spoke about people now missing from their lives but who at one time had passed over their hearts and left a shadow.

"Friede turned to me and smiled as if to say, ‘All these old people and their memories; I will make a thousand better ones.’ Watching them, I understood that I was an outsider looking into their world. It was a universe of memories from a collapsed galaxy. It was odd that even though their lives had been so horribly altered by the war and their present filled with hunger and pessimism, they were still thankful for being alive. . . ... Their hearts ached for a finished era, dead family, friends and lovers."

130: "[When midnight came and the bells peeled from the churches which hadn't been obliterated in the bombing the residents] came out onto the balcony. They held lit candles to confront winter’s darkness. With one arm around Friede and my other hand holding on to a burning taper, I heard the bells across the city strike midnight. . . . Eventually, the clamour from the bells drifted away and all that remained was an expectant emptiness in the air. A male voice stirred from four apartments away. He began in a low, strong tone, singing the words to ‘Silent Night.’ His voice was joined by other singers until the melody reached our balcony; we also sang Brahms’ lullaby to mankind [in hope revelry and thanksgiving that the war was over]. The tune travelled deep into the blackened city and dissipated into the Elbe River, where it drifted out to the cold, dark Baltic Sea."

2. In I, Keturah, Ruth Wolff (b 1932, Massachusetts) writes of a Christmas somewhere in rural America, but not too far from a city, sometime between the WW I & WW II, from the perspective of an orphaned teenaged girl, who has at long last been taken in by a loving, elderly couple:

74: "I shall always remember my first Christmas at the Dennys'. Late in November Mrs. Denny baked her fruitcakes. Candied fruit was snipped into tiny pieces walnuts and hickory nuts we had gathered in the October woods were cracked and shelled; the heavy dough was stirred with big, wooden spoon in an earthenware mixing bowl lined with tiny cracks of age. while the cakes were baking the house was charged with a wonderful spicy odor. Coming in from the cold outdoors and smelling the cakes rising in the oven was to sniff of an exciting time to come.

"Mrs. Wayburn came over to help with the cookies . . . we rolled out the floured dough and cut it in the shapes of stars, wreaths and animals, sprinkling the tops with pink sugar, cinnamon drops and raisins . . . ."

Photo ~ January 4, 2012

75: "Reading was put aside as we pored over mail - order catalogues. Mrs. Denny would slyly let Mr. Denny know what she wanted by lingering over a certain page. In the same way he made his desires known to her. . . . The Dennys had bought clothes for me . . . warm dresses, a coat, shoes, three pairs of lisle stockings, underwear, and a green felt hat. The morning the boxes arrived, I tried everything on for Mrs. Denny, who saw that it fit and approved. . . ."

76: "Two days before Christmas, Mr. Denny and I went out to the woods to cut a tree for the bay window in the parlor. There was a light snow on the ground. Mr. Denny whistled as we walked through the snowy woods, his cheeks rosy, an ax over his shoulder. He knew the tree he wanted. He had not taken it the year before, wanting it to grow a bit more.

"Surrounded by the snow, the fir tree stood strong and beautiful in the winter afternoon. Mr. Denny gently touched the feathery branches. I could see he hated to cut it down.

" 'But think of the pleasure it will give us,' he said, having to have a reasonable excuse to take it from its native woods. . . .

" 'I'm sure this tree never dreamed it would grow up to be a Christmas

tree . . . . ' "

78: "After the tree was set up in the bay window, we popped corn, strung it, and wound it around the branches. Mrs. Denny brought out a box of ornaments she kept from year to year, carefully unwrapping them from tissue paper, and Mr. Denny and I hung them on the tree. Last of all, the little candle holders were clamped on the tips of the branches and a red candle placed inside each one. Just at dark on Christmas Eve Mr. Denny touched a match to each candle. When they were all lit the little green tree was more beautiful than it had been in the snowy woods. Its candles burned twice, once on the branches and again in the windows. I thought how proud the little tree must feel standing there with it strings of popcorn, its glistening ornaments, its reflected candles It had come out of the lonely woods where it had been showered by rain, warmed by sun, decked with winter's snow where it had shivered in the sharp cold holding up its branches under the darkest sky. And I felt a kinship toward the tree, its origin shrouded in mystery as my own."

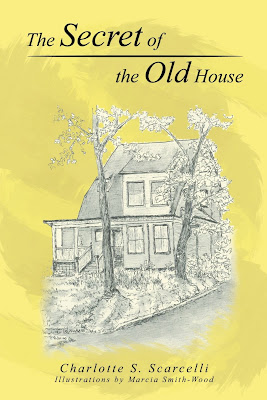

Photo ~ December 12, 2011

80: "The basement of the church was hung with red and green crepe paper. In the center of the room stood a great tree lighted with white candles. Around it the folk of the countryside gathered and sang carols, while the candles brightly burned and reflected on their upturned faces. The voices rose until it seemed as if the ceiling would be lifted by their joyful praise. around the tree stood men who wrestled with the earth from dawn to dusk, women who spent their lives in hot kitchens, in cleaning big, old - fashioned farmhouses, in rearing children; old folks with lined faces hand relieved of the reins of work; young people who would follow in their parents' footsteps, others who would go beyond the limits of their birthplace to seek their fortunes, who would never spend another Christmas Eve around the big tree at the church; wide - eyed children clinging to grown - up hands, trying to catch the words of the songs; babies soundly sleeping in strong arms."

3. In The Skeptical Feminist: Discovering the Virgin, Mother, and Crone, Barbara G. Walker (b. 1930, Philadelphia) describes the "typical middle - class American Christmases" of her youth:

45: " . . . not unique, not sacred, not particularly religious. They could easily be criticized as commercial, and overindulgent. My mother used to say, 'Christmas is for the children.' "

to be continued in January . . .